The Church and the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

597 AD - present

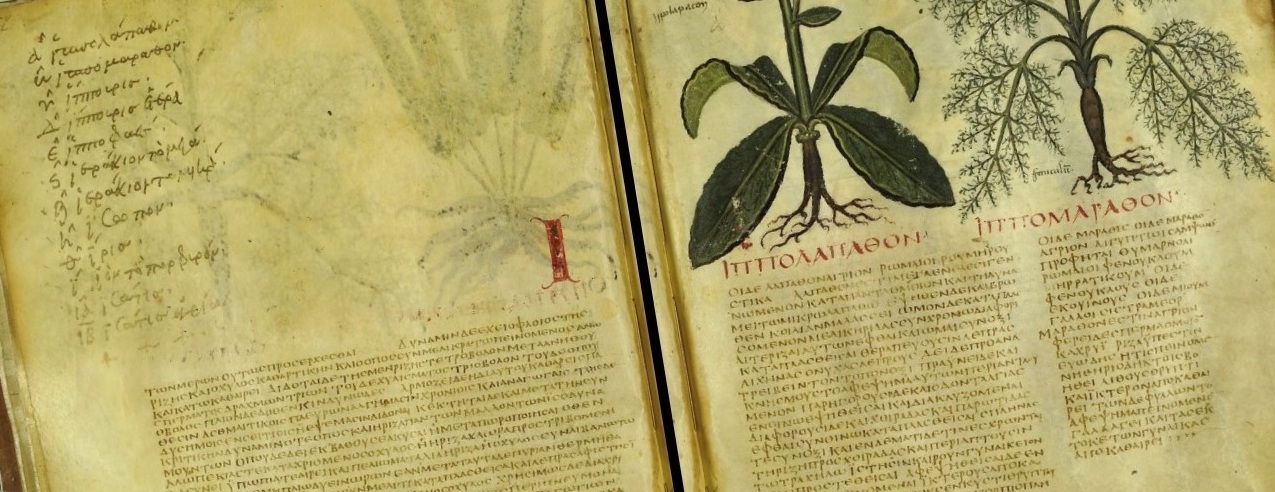

Photograph: Composite. Left: Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, who reigned as Ruling Queen 911-918 CE, depicted n the thirteenth-century Genealogical Chronicle of the English Kings, British Library Royal MS 14 B V. Public domain. Right: Queen Æthelflæd in the cartulary of Abingdon Abbey (British Library Cotton MS Claudius B VI, f.14), Wikimedia Commons. It was very unusual for a woman to reign and be brilliant at military strategy during the medieval period, but Æthelflæd was such. She was the eldest daughter of King Alfred the Great. She was succeeded by her daughter Ælfwynn.

Introduction

The selection of perspectives on church history in this section — Church and Empire — has been guided by three factors: (1) to demonstrate that Christianity has not been a “white man’s religion”; (2) the study of empire as a recurring motif in Scripture by recent biblical studies scholars; and (3) explorations of biblical Christian ethics on issues of power and polity, to understand how Christians were faithful to Christ or not. Christian relational ethics continues a Christian theological anthropology that began with reflection on the human nature of Jesus, and the human experience of biblical Israel.

This section explores the experience and activities of Christians under the Anglo-Saxon regimes in Britain. This includes the Norman invasion of 1066, which provoked Anglo-Saxon resistance. English common law reflects Christian influence, which is important to U.S. law. Anglo-Saxon Christian mission was also historically important; J.R.R. Tolkien called it “one of the chief glories of ancient England, and one of our chief services to Europe even regarding all our history" (edited by Alan J. Bliss, Finn and Hengest: The Fragment and the Episode. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1982, p. 14).

Messages and Resources on the Church in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms

This is the tenth of our 11 part video series exploring Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, with references to The Hobbit, The Silmarillion, and other books in the Legendarium. Sample the video, and check out our Tolkien page. Part 10: Lessons on Power from The Shire, Rohan, and Gondor looks at lessons about power and leadership from those three contexts. The Scouring of the Shire teaches us why we should resist "plantation capitalism," which has ethical relevance for the British Industrial Revolution. Rohan has lessons about migration, conflict, treaties, and peace, which was influenced by the the history of the Anglo-Saxons settling Roman Britain. Gondor sifts its legacy from Numenor: an influential blessing at first, an imperial terror at the end. This reflects Tolkien’s ethical critique of the development from Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to British imperialism. Numenor had Ruling Queens, as the Anglo-Saxons did with Æthelflæd and Ælfwynn. The Anglo-Saxon Christian resistance to the Norman Invasion of 1066 is also very important, since it influenced the Magna Carta (1215) and the Charter of the Forest (1217).

00:10:36 The Shire

00:25:57 Rohan

00:38:14 Gondor

00:53:25 The Biblical Theme of Empire

01:07:08 Women Ruling and Leading

01:26:45 Land and Property

Other Resources on the Church in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: How the Church Shaped the Empire

Wulfstan (1008 - 1095), Bishop of Worcester (1062 - 1095) (Wikipedia article). The last Anglo-Saxon Christian bishop before the Norman invasion of 1066, who continued into the Anglo-Norman period. Wulfstan opposed the slave trade and is generally credited for the gradual Christian victory over chattel slavery in England, even though there was no formal legal policy passed by the crown or Parliament until 1833.

William Harrison, Description Of Elizabethan England, 1577 (from Holinshed's Chronicles). In chapter 1, Harrison attests to the abolition of slavery on the “soil” of England:

“As for slaves and bondmen, we have none; nay, such is the privilege of our country by the especial grace of God and bounty of our princes, that if any come hither from other realms, so soon as they set foot on land they become so free of condition as their masters, whereby all note of servile bondage is utterly removed from them…”

Benjamin Thorpe, Ancient Laws and Institutes of England: Comprising Laws Enacted Under the Anglo-Saxon Kings from Æthelbirht to Cnut, with an English Translation of the Saxon; the Laws Called Edward the Confessor's; the Laws of William the Conqueror, and Those Ascribed to Henry the First. Public Domain | Google Books, 1840.

Joseph H. Lynch, Christianizing Kinship: Ritual Sponsorship in Anglo-Saxon England. Cornell University Press | Amazon page, Aug 1998. Among pagan Germanic peoples, kinship was very important to how families and groups organized themselves. Christian faith expanded definitions of kinship and changed sexual mores. Lynch covers the period 597 - 1066.

Patrick Wormald, The Making of English Law : King Alfred to the Twelfth Century, Volume 1: Legislation and its Limits. Wiley-Blackwell | Amazon page, 1999. “The first full-length account of the Old English law-codes for over eighty years, and the first that has ever been published in the English language. It is designed to be both an authoritative work of reference for scholars seeking enlightenment on particular legal manuscripts or texts and a coherent account of how the corpus of Old English law from the seventh to the twelfth century came to subsist and survive. Part I opens with an account of the historians of early English law, including the immortal F. W. Maitland (1850-1906) and Felix Liebermann, author of the definitive edition of the law codes (1898-1916). It then provides the most detailed examination English of law and legislation on the European continent in the post-Roman era and of the earliest Anglo-Saxon legislators in the seventh century. This sets the scene for the law making of King Alfred and his successors.”

Carla Spivack, To "Bring Down the Flowers": The Cultural Context of Abortion Law in Early Modern England. William and Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice, Volume 14, 2007 - 08. Spivack notes that King Alfred the Great, the practical source of English common law, valued the slain fetus at half the weregild, or man-price, of the pregnant mother. This means that the fetus was not valued at full personhood. It is also significant that Alfred does not recognize the Hebrew vs. Greek manuscript differences, which means he was likely dependent on the Latin Vulgate’s understanding, and estimating.

Barbara Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England. Routledge | Amazon page, Nov 2015. Yorke surveys the period before 600, just at the time of the mission of Augustine of Canterbury and the conversion of King Æthelbehrt.

Rowena Willard-Wright, Saxon Easter Customs and Where They Survived. English Heritage, Mar 24, 2016. These customs survived the Norman Conquest of 1066, that is - a good example of how Christians preserved aspects of culture worth remembering, despite political turmoil.

Tom Lambert, Law and Order in Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford University Press | Amazon page, 2017. Lambert shows that the more powerful state of King Æthelbehrt was due to his desire to govern in a Romano-Christian way, which reduced blood feuds and instead emphasized restorative justice compensation payments akin to Jewish restorative justice practices from Exodus 21. King Alfred the Great wrote a commentary on Exodus, explicitly, and drew upon Æthelbehrt and other prior Christian Anglo-Saxon kings, in his own Book of Judgments (Doom Book). “The focus of the volume is on the maintenance of order: what constituted good order; what forms of wrongdoing were threatening to it; what roles kings, lords, communities, and individuals were expected to play in maintaining it; and how that worked in practice. Its core argument is that the Anglo-Saxons had a coherent, stable, and enduring legal order that lacks modern analogies: it was neither state-like nor stateless, and needs to be understood on its own terms rather than as a variant or hybrid of these models. Tom Lambert elucidates a distinctively early medieval understanding of the tension between the interests of individuals and communities, and a vision of how that tension ought to be managed that, strikingly, treats strongly libertarian and communitarian features as complementary. Potentially violent, honour-focused feuding was an integral aspect of legitimate legal practice throughout the period, but so too was fearsome punishment for forms of wrongdoing judged socially threatening.”

Patrick McBrine, Biblical Epics in Late Antiquity and Anglo-Saxon England: Divina in Laude Voluntas. University of Toronto Press | Amazon page, Jun 2017. Anglo-Saxon Christian poets and prose writers Juvencus, Cyprianus, Arator, Bede, Alcuin, and others appear to have been valued by Christian audiences for over a millennium.

Annie Whitehead, Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England. Pen & Sword Society | Amazon page, May 2020. Anglo-Saxon Christianity was notable for how women rose to power. “A royal abbess educated five bishops and was instrumental in deciding the date of Easter; another took on the might of Canterbury and Rome and was accused by the monks of fratricide. Royal mothers wielded power: Eadgifu, wife of Edward the Elder, maintained a position of authority during the reigns of both her sons. Æthelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, was a queen in all but name, while few have heard of Queen Seaxburh, who ruled Wessex, or Queen Cynethryth, who issued her own coinage. She, too, was accused of murder, and was also, like many of the royal women, literate and highly educated.”

Daniel Cote Davis, Charles Coulombe on Kingship and Tolkien. EWTN Great Britain, Jun 8, 2023. Coulombe argues for the dynastic monarchy from Judaism and God’s covenant with David, which culminates in Jesus Christ. Historically, the Anglo-Saxon monarchy was Catholic, and retained certain Catholic features when other European monarchies shed that influence. Coulombe additionally argues that Tolkien’s vision of Aragorn as an ideal king is as the chief layman. Coulombe argues that Aragorn is like a Charlemagne because he unites and restores an older kingdom. The argument is both tantalizing and troubling, because it is more romantic than morally and ethically grounded, although the interview is far too short. The interview does not mention how the kings in the Ancient Near East often proclaimed debt-jubilees so that the peasants could be free from the oligarchic nobles.

Other Resources on the Church in the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: How the Empire Shaped the Church

George Monbiot, A Land Reform Manifesto. Monbiot.com, Feb 22, 1995. Monbiot narrates the history of English land law, which took a pivotal turn when William the Conqueror arrived in 1066, took land from the people, and legally claimed it as his own, while functionally doling it out to 180 barons. This has enormous legal and social significance for the United States because it drove migration to the American colonies, but also served as the background to John Locke’s theory of private property. On the one hand, Locke sought to find a new basis for individual private property rights over against the state. On the other hand, Locke gave up too much ground, giving no space for the community to manage land and waters in common.

“It was not until Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries that large-scale dispossessions began. In selling their land to urban businessmen, he created a new, peculiarly rapacious landed class, which wasted no time in realizing the value of its assets by seizing the commons and evicting the commoners. The Civil War was essentially a battle between these new lords of the land and the older landed order, and the victory of the former accelerated the adoption of their methods by the latter. In the 18th and 19th centuries the institutionalized theft of the enclosures was formalized by hundreds of acts of parliament.

By the time the Parliamentary Enclosures ended, most of the population was living in the towns, many in misery and squalor, and the land was in the hands of a tiny number of its inhabitants. Today one per cent of the people own between 50 and 75 per cent of the land. It is impossible to be precise, as the landlords have successfully resisted a census since 1875. In Scotland, the enclosures – or Clearances – were both more rapid and more complete than in England. Thousands died when they were dispossessed, tens of thousands were forcibly loaded onto ships and sent to the colonies. Today, half of Scotland is owned by 600 people, and the thieves of our common inheritance are the undisputed lords of the land.”

Roy Casagrande, American Capitalism and the British Empire - 1492 to 1776. Collective History, Mar 17, 2024. How the British imperial elites decided to become the first drug-based empire using tobacco by addicting their own citizens with a product grown on land stolen from Native Americans and grown by labor stolen by indentured servants and slaves. English explorer John Rolfe figured out how to grow tobacco in the Carolinas.

Church and Empire in Europe: Topics:

This section explores the experience and activities of Christians under various European regimes: the Roman Empire 313 - 800, the Celtic Kingdoms 431 - 1798, the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms from 597, the Eastern Roman Empire 800 - 1453, the Latin Kingdoms 800 - 1787, and the Slavic Kingdoms 988 - 1917. See also our page on The Myth of Christian Ignorance, for resources contesting Christian faith as anti-science, politically backward, etc.

Church and Empire: Topics:

This page is part of our section on Church and Empire. These resources begin with a biblical exposition of Empire in Church and Empire and the meaning of Pentecost in Pentecost as Paradigm for Christianity and Cultures, then grouped by region: Middle East, Asia, Africa, Europe, Americas, then Nation-State, with special attention given to The Shoah of Nazi Germany.